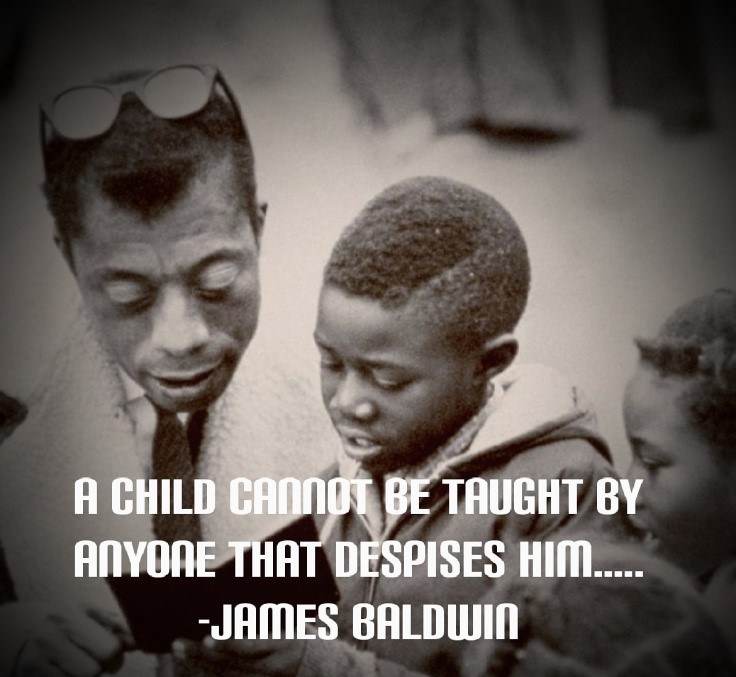

History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer principally to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, that we are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways. History is literally present in everything we think and do. James Baldwin

This quote, by Black Civil Rights activist James Baldwin, resonated with me following our recent Provocations lecture. A vast amount of information was provided and discussed during the session but to acknowledge our own history was resounding. This led me think about our habitus and hidden curriculum within the teaching profession and how our own history effects our philosophy.

Bourdieu (1986) discusses habitus and the conception that all human action connected the relationship between an individual’s thoughts and actions; habitus, and the overall objective world (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990). Habitus enables us to interpret experiences that we encounter in life, how to deal with specific situations or events and why we may feel awkward or uncomfortable in certain circumstances (Deerness, 2012). Our own habitus and beliefs are formed through our life experiences, incorporating how we speak, dress, our manners and life’s expectations, thus enabling us to reflect on how we might incorporate them, either positively or negatively, into the hidden curriculum. This is also our ‘history’, the history deep within each of us that is rooted in our upbringing, life experiences and our unconscious.

Philip Jackson (1968) identifies the hidden curriculum as the unwritten and unintended lessons that students learn at school, the “unpublicised features of school life” (Jackson, 1968, p.17). The understanding is that students absorb the implicit messages of social and cultural behaviour that are communicated from teacher to classroom. These messages can range from how to interact with peers and teachers, what ideas and behaviours are considered acceptable to how we perceive different races, groups, gender or social classes (Winter & Bailey, 2012).

I recall as a student, at secondary school in Northern Ireland, the hidden curriculum of my school was historically sexist. The history of the past reflected on the present. PE sessions were divided by gender, with girls playing hockey and boys playing football and rugby. During the summer boys and girls combined to compete together in athletics. At this time, the late 1980’s/early 1990’s, the school did not permit girls to compete in javelin as it was considered inappropriate. I thought the rule was completely wrong and dismissed females as the weaker sex. Another gender specific rule stated that girls only competed in sprint trials up to 800m, however the boys could run greater distances. I maintain that these archaic rules were based on the traditional historical gender beliefs that girls are the weaker sex, compared to boys.

As aforementioned I was raised in Northern Ireland, a country with a violent past and segregated on the grounds of religion, Catholic and Protestant. I went to a predominantly Protestant school in a low socio-economic area. We were divided from the Catholic population at school, in our community, Church and practically every aspect of our lives. The population of Northern Ireland in 1991 was almost significantly majority white, in fact 99.75% (Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency, 2015). I therefore had little or no opportunity to be associated with other religions, races or social groups besides my own. For some members of society this would result in an extremely fixed mindset towards people of other ethnicities and religion, however for me it was always a dream to travel and immerse myself in other cultures and communities. Thus, I immigrated to New Zealand and settled in Auckland, the fourth most ethnically diverse country in the world (Statistics New Zealand, 2013). It was living in an ethnically static country such as Northern Ireland that positively influenced me to want to live and work in an ethnically inclusive country, ensuring that everyone was treated equally and without prejudice.

Each of us, as teachers, have our own past experiences and life lessons learnt and each of us will bring this history and habitus to school, incorporating it into our own teaching philosophy. However, we must ensure that these messages are positive and culturally responsive, inclusive and equitable; ensuring that students are nurtured and respected through our history and into their future. It is imperative we, as future teachers, provide a safe learning environment in which students are positively influenced to attain personal achievements, regardless of gender, ethnicity, social class etc and where inclusive, participative, contextual teaching promotes inspired, engaged and co-operative learning.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital”. In I. Szeman & T. Kaposy (eds.), Cultural theory – An anthology (pp. 81-90). West Sussex, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bourdieu, P. & Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London, England: Sage Publications.

Deerness, S. (2012). Just habitus: Why habitus matters in socially just teaching. In M. Stephenson, I. Duhn, V. M. Carpenter, & Airini (eds.), Changing worlds, critical voices and new knowledge in education, pp.126-137. Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson.

Jackson, P. W. (1968). Life in classrooms. New York, USA : Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency. (2015). Census 1991 [Website]. Retrieved April 14, 2019, from NISRA website : http://www.nisra.gov.uk/census/previous-census-statistics/1991.html

Statistics New Zealand. (2013). Estimated resident population (ERP), sub national population by ethnic group, age, sex, at 30 June 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from Statistics New Zealand website: http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE7512# ffff

Winter, J., & Bailey, I. (2012). Researching the hidden curriculum: intentional and unintended messages. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 37(2), 192. doi: 10/1080/03098265.2012.733684

It’s certainly very easy to become set in our ways as a result of our upbringing. Sometimes our history is so deeply implanted in us that we develop the misconception that our way is the only right way and we neglect to see other peoples’ perspectives. Being overly staunch in what we believe to be right and closed off to diversity can be so detrimental to the relationships which we build in the community around us. This makes it so essential for us as teachers, in a profession that is largely centred on relationship building, to recognise that our students’ beliefs and actions were formed as a result of their upbringing, just as ours were. Unfortunately many teachers become so caught up in the authoritarian side of teaching, however understanding the perspectives of our students will allow us to adopt a pedagogy of care and build positive relationships which bring out the best in our students. I completely agree with you that it is so important for us to be aware of our hidden curriculum so that we can channel our past experiences to positively influence students’ lives.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your thoughts Sarah! It is interesting to hear the experience of schooling from a different part of the world. It is easy to become set in our ways, and stick with the status quo and what is comfortable. I think that is awesome that you had the outlook and goal to see other parts of the world and didn’t accept the status quo of your environment. How inspiring.

I grew up around several different ethnic groups of people. My best friend through primary was filipino. I don’t think I truly understood a difference in ethnic groups until I was I secondary school, I put this down to the innocence of being a child and seeing another person for exactly that, a person – boy or girl, black or white. At the end of the day we are all human. Sexism and other negative attitudes are learnt ideals, if we can learn to be negative, we can definitely learn to be positive.

You absolutely hit the nail on the head with our responsibilities in terms of equality and inclusion. Our classrooms need to be a safe place for students, we need to demonstrate values and behaviour that is accepting of people from all walks of life. If students do not see this being demonstrated, how will that ever change how they behave and accept others?

Thank you for the inspiring read.

LikeLike

Hello SW,

James Baldwin’s quote really caught my attention to read this blog post, nice opener. Also, I found the personal input really interesting about going to school in Northern Ireland. So strange to think that girls were not permitted to compete in the javelin and could only compete in races of up to 800m in your school, but that being said it is not surprising seeing that discriminatory ideas towards females physical capabilities still exist in almost every part of the world today. When you mention how girls played hockey and boys played football and rugby, I think this relates to some idealised norms still very prevalent today as I still can see there are different sports boys and girls are guided into through the hidden curriculum and so-called social norms

Furthermore, you made a number of interesting references to the history and your experiences of Northern Ireland, such as that about the Catholic and Protestant segregation as well as the ethnic makeup of the area while you grew up. It is interesting to hear how the history and your experiences have shaped your decisions and attitudes, and I could not agree more with the emphasis you put on ensuring a positive culturally responsive message in teaching.

LikeLike

Your blog really resonates with me as I feel that the principal contributor to my personal positioning and world view is my upbringing in apartheid South Africa and the overt racism which surrounded me daily. I attended an all-girls, white, state school where I received a high quality albeit traditional education. However, I was surrounded by young black people who were deprived of an adequate education. From my earliest years, I was acutely aware of the extreme racism which impacted all black people; people of my own age and ability who through political, financial, social and educational deprivation were being robbed of their basic human right to succeed.

I grew up in an intensely liberal household and my family were deeply opposed to apartheid. We felt frustration and helplessness in the face of an extreme and violent oppressor.

Witnessing this injustice, oppression and violence in my formative years has left an indelible mark profoundly ingrained on my being. Anger and deep opposition to all forms of discrimination has been the result, along with complete commitment to equal rights and opportunity for all.

It is this history and habitus that I will bring to my classroom – an absolute undertaking to create a classroom where children of all cultures will be treated equally, fairly and with no discrimination. I will show the utmost respect to all students by building knowledge of their culture, values and beliefs, and I believe creating this type of environment is a key role of a teacher.

LikeLike