“The shift to a cleaner energy economy won’t happen overnight, and it will require tough choices along the way. But the debate is settled. Climate change is a fact. And when our children’s children look us in the eye and ask if we did all we could to leave them a safer, more stable world, with new sources of energy, I want us to be able to say yes, we did!” (Obama, 2014).

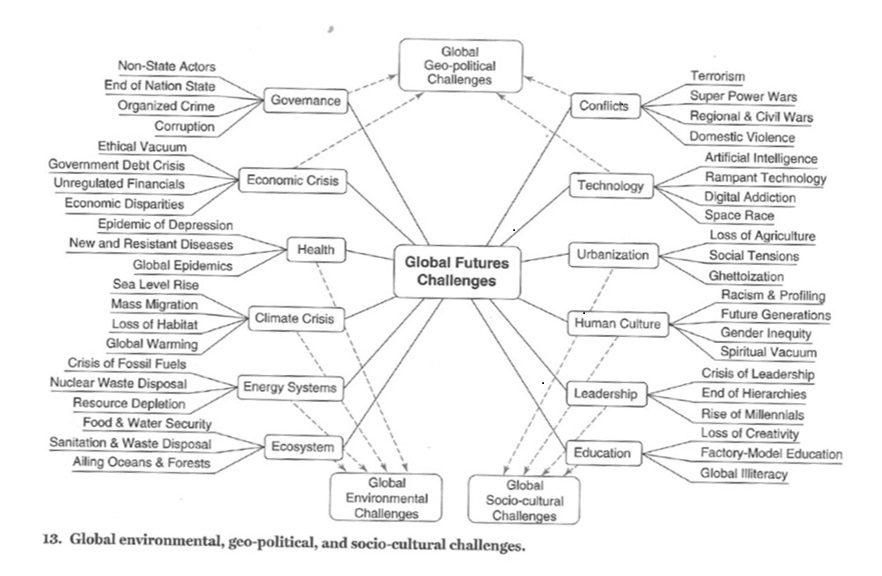

Following a recent lecture of Future Focused Education, I began to think about the important issues relating to humankind and how education could hold the key to providing sustainable solutions for ‘wicked problems’ in society today, include Climate Change and its global effects.

Climate change is an environmental worldwide problem requiring real life solutions, together with developing education to inform, understand and change ideas, thus providing a safer, sustainable future for everyone. In 1896 Swedish physicist Svante Arrhenius, first described problems relating to the greenhouse effect. The focus of his findings is still debated today (Cossia, 2011). Understanding the challenges and consequences of climate change, including rising global temperatures and extreme events such as flooding and severe weather is a prerequisite for facing the challenge of providing a solution to these issues; and many more. Future focused education must be comprehensive and multidisciplinary, especially in relation ‘Climate Change Education’, and a focus of young people throughout schools.

The challenges of the twenty first century will increasingly require students to consider and interpret the pathways that humanity has taken to date. Students will be confronted with the effects of climate change throughout their lives and, as the decision makers of the future, will be instrumental in shaping society and future developments throughout the world. Education is stated to be an integral aspect of the transformation to a sustainable society. (Bussey, 2002).

Educators should be proactive in their teaching to providing solutions to climate change. Bussey (2002) states that the current education system is “caught up in archaic modes of organisation and learning”. Students learn the world through their hearts, with their heads following later. It is with this in mind that a strategic and real-time solution must be established into every students learning, encompassing skilful and authentic information and a desire to research, inquire and transform.

We, as teachers, must educate students to ‘care’ about the environment, climate change and how education is the key to success to alleviating this and other ‘wicked’ problems around the world. Future focused education combined with cross-curricular collaborative learning would ensure that it is not just a science or geography related topic but could include many other subjects, working together, ensuring student agency and development of thinking skills to source solutions to real life problems.

How easy will this be to implement? We will find out soon enough, when we, like so many before us enter this profession as Educators.

References:

Cossia, J. M. (2011). Global warming in the 21st century. New York, USA : Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Bussey, M. (2002). From youth futures to futures for all: Reclaiming the human story. In J. Gidley & S. Inayatullah (Eds.), Youth Futures : Comparative Research and Transformative Visions. Connecticut, USA : Greenwood Publishing Group

Obama, B. (2014). President Barack Obama’s State of the Union Address [Website]. Retrieved on June 1, 2019 from The White House website: http://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press/2014/01/28/president-barack-obamas-state-union-address lsdprio